Rocky Bleier—Interview With the Wounded Vietnam War Veteran

By JOHN INGOLDSBY

March, 2011

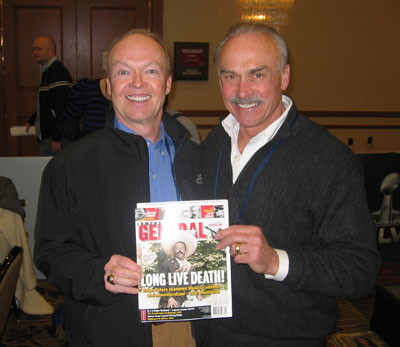

John Ingoldsby, left, talks with Rocky Bleier on Radio Row during Super Bowl Week in Dallas.

This issue of Armchair General featured an interview titled “10 Questions: Rocky Bleier.” This is the uncut version of that interview, presented as an online extra for Armchair General readers —and fans of Rocky Bleier!

I am sure you must find it hard to believe that last August 20th was forty years to the day from when you were wounded twice during the ambush in Vietnam, which earned you the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star. What are your memories of that time forty plus years later of that day?

BLEIER: It would be the experience on that day of not knowing what was going to happen, or what happened actually the night before. It’s always nice when you have information that you find out later what exactly took place. But, I remember our company was in reserve and our feelings when our sister company got hit. Obviously, like often in the Military, it was a day of being on alert, and we were ready to go in and support. It was always hurry up and wait. We were on an LZ (Landing Zone) and waiting for the helicopters to come in, and they came in late in the afternoon and took us out and flew us down into the field. I can remember that then we collected there, and we went out that night to support our sister company and to get them out of that area. But there was firing going on. There were tracers going through the sky as we were working our way through the jungle that night. And I can remember helicopters getting shot at, going down, and we finally got there, and there was a lull in the action. It was late at night, because it was dark, so it had to be around 9:00. And then we were to pull front and rear security and move them out. Those who were left are those bodies and wounded who didn’t get out on the choppers, we were to help them out.

We ran into a slight ambush and ultimately the word was to leave our comrades who had died behind, and get everybody else out, and two days later we were to come back. So our mission was to go back and locate those bodies we had left behind so that we could secure the area and have helicopters come in obviously to extract them. But we didn’t know that – we were just on patrol. And with all the activity that’s going on, and not knowing what we ran into or who was there or what – all the information – everybody was on pins and needles until that morning when we ran into another ambush and when I got wounded the first time in the field. And so it was like, “Oh, man, this is finally hitting”. Now we’re in a firefight – guys screaming, yelling back and forth. There was a radio man who left his radio behind so I could hear part of the communication that was going on to the rear to hopefully get some reinforcements, not knowing what was taking place, and so it was that kind of chaos happening. And eventually they got out us of there, and I with a medic, went back to our Commanding Officer, who was just behind us, and then the rest of the guys came in, and we got hit the second time. Ultimately, what we ran into was a regiment, or at least that was the information that we had. They didn’t know what they ran into, and sometimes, when you don’t have all the information, maybe you’re better off.

Whatever contact we had with them stopped and they retreated, which allowed another platoon to come in and get us out of there and eventually get us to the aid stations. So those were all the actions that were taking place at that time. And you were just on remote, reacting to the situation as it took place. Hopefully, you would survive and get out of there or help would come.

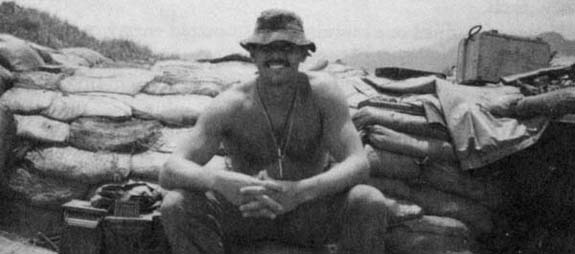

Bleier in Vietnam (Courtesy, Rocky Bleier)

Quite a story, and thank you for explaining it in such detail. And, speaking of help, in your book “Fighting Back,” you reference the fellow soldier who carried you 500 yards to safety. Did you ever find out who that was?

BLEIER: No, I never found out. No one ever came forward, and again, I think it was a time of reaction. As I explained in the book, the reinforcement platoon came in, and someone filtered out of that platoon, sliding to where I was and asking, “Rock, you all right?” And I said, “Yeah.” “Oh, good,” he said, “Because we heard that you’re the Commanding Officer, since Captain Murphy and you guys got killed. “Don’t worry, don’t worry, we’re going to get you out of here. You’ll be the second guy out. The Captain’s got to go first, but stay in.” I said, “Okay, fine.” Then they carried us out of that area, and we were fighting to get to where we are, and it’s all that stuff that takes place and they were tired. So they carried me maybe a third of the way. And then they said, “Don’t worry; we’ll get a stretcher in here, and somebody will come back.” Then two guys picked me up and they carried me fireman-style between their shoulders. But they got tired, obviously; they were dragging me and I am just dead weight. So they set me down and said, “We’ll send a stretcher back, don’t worry.” Then, all of a sudden, out of the darkness, someone reached down and held me up and said, “I got you soldier” and threw me over his shoulders and carried me the rest of the way to the bottom of the hill. I needed a stretcher, and obviously they didn’t have one. But, I’ve told that story, and obviously it was in the book, and no one has ever stepped forward to claim that action or not. But, you do think, and I use that story as an example comparing team sports and the military, where under a situation, you’re just another one of the guys, and you react and do the things that you would do with anybody else. That was the reaction., and you think about it – and that was the late part of the 1960s.

Are you still in touch with any of your comrades and arms from that time?

BLEIER: That’s an unfortunate thing for that war because it basically was a replacement war, so you came in as new recruits — new meat — and you’re the new guy. So the only thing you shared was the commonality at that time. It wasn’t as if you came from the same hometown or if you’re playing together and you understood and knew one another or you had some history. So you were only on a first name basis, if that, at best, and you left as an individual. Whether you served your full time and then flew home, or you got wounded like many of us and then flew back by yourself. So, to answer that question, no, not anybody specifically I served with in Vietnam. I have run into a couple of people over the years that I served with. But that dissipated and we lost touch, and I don’t know where they are. Some of the people I do stay in touch with are people I was with at Ft. Riley in Kansas after I came back. We had a couple of guys that I met there, and we stay in touch. There was one guy in the eastern part of Pennsylvania that was in my Company at the same time, and so we periodically stay in touch. So that’s about it, and that’s the shame of that war.”

Actually, Rocky, that leads right into my next question. During your grueling rehabilitation, who was the single most inspirational person for you during that time?

BLEIER: I don’t know if there was any one person that was an inspiration. There are people that created an opportunity or some hope, and I tell the story that when I was in the hospital, and the doctor said I’d never be able to play this game again given my wounds and the damage to at least my foot from his perspective. It kind of depleted my hope a little bit since it was not the answer I was looking for. Then right after that, I got that postcard from Mr. (Art) Rooney (Steelers Owner) who said, “Rock, the team’s not doing well, we need you.” And the point was not if they needed me, but I like to tell people it’s that they had an interest. He took the time to write the postcard and said, “Hey, we need you, come back.” So that gave me the hope or inspiration to be able to do it. The driving aspect of my life, my career, is that it was something I wanted to do. I wanted to go back and play football, and the reason was because it gave me a certain status, at least from my perspective, something different than what other people did, and I liked playing the game. I liked what football had given me as a goal to be able to achieve. So that became the driving force. It wasn’t as if I wanted to do anything else with my life, so I could focus on those things that were necessary to come back and at least play or try to play. That was the biggest question — to try to play since I can remember thinking to myself, “Okay, fine, you got to do everything you can so that later on you don’t go saying that I wish I would have done more, ran more. You’ve got to use all your energy within the confines of where you are to hopefully get to the next level, whatever that may be. So that became a driving force.

The day after you and I met during the last Super Bowl week (2010), a news release was issued that NFL stars including you are supporting injured military. Can you tell me a little bit about your role with that effort?

BLEIER: There are studies taking place on head trauma, and within the NFL regarding the early onset of dementia, and of course that is primarily the type of injuries that are being received in Iraq and Afghanistan with our troops. That rattle of the humvees, the shock to the head, concussions that happen, those are the studies taking place, in this case at the University of Minnesota Depression Center for head injuries. It’s the same thing that happens in the world of football. The trauma head injuries ultimately can lead to depression, which ultimately can lead to suicide. So we know that statistically suicides have been up among returning veterans, as well as suicides being part of a depressed mood. What we’re trying to bring to the public is an awareness factor that when you deal with and see depression, there’s help. Here are some of the signs and be aware because it can possibly lead to suicide. So here are the numbers to call and here is the reaction. That’s what we’re trying to do, and it worked out well for us to get that story out.

Are you now involved formally with any other Vietnam Veteran’s organizations and/or U.S. Army Department of Defense efforts or projects?

BLEIER: You name it, I’m involved in it. We have a plate full of things that are going on. For instance, the National Wheelchair Games that are going to be in Pittsburgh in 2011 – Franco Harris and I are chairing those games. I chaired them 11 years ago, so we’re in the planning stages there. There is an awareness bicycle ride for wounded warriors that is coming across the country this summer, and they’re coming to Pittsburgh in July, and we’ll get involved for the couple of days that they’re going to be here, which is one of the Media Centers on their way across the country. But, whatever has to deal with the Military, we are involved in it. Also, here in Pittsburgh, I’m involved in an organization called NAVOBA, which is the National Veteran Owned Business Association, that is promoting returning veterans and why corporate America should invest their time and energy in hiring these returning veterans because of the experience that they bring – management skills, and all the things that make not only a good employee but decision-making members. So, yes, there’s a lot on the horizon that we get involved in.

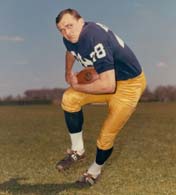

During his time at the University of Notre Dame, Bleier won one national championship and served as a team captain during his senior year. (Courtesy, University of Notre Dame)

Turning to your football career, you won one national college championship and four Super Bowls, and along the way you played in two of the most famous football games of all time. The first one in 1966, you are an All American running back at Notre Dame, and you played in the epic 10-/10 tie game against Michigan State. What is your strongest memory of that game?

BLEIER: My strongest memory was that it was deemed “The Game of the Century.” It was the first tie and the two number one ranked teams got the chance to play one another close to the end of the season. It was Michigan State’s last game; we had one more with Southern Cal. For that mythical national championship, and that’s what it was at the time since there were no bowl games for Notre Dame, no playoffs as we have them today. There were a lot of All-Americans on both teams, and my goodness, there were about 19 or 20 people that went off and played in the pros from those two teams.

So it was a very talented team, but it was also a coming out of college football and the black player in college football in major divisional schools at the time. In 1966, there were no black players at southern schools; there were no black players in Texas or Alabama or Arkansas or Mississippi. So Duffy Doherty got Bubba Smith to come up to Michigan State, and Bubba brokered that to field Gene Washington and Clint Jones, who all came out of that part of Texas, in Beaumont. The three of them went up there and all three became All-Americans.

But that was a crucial game. Now, we didn’t know it at the time, the impact of the game was an afterthought. It was just the fact that we were playing the game for the National Championship up there, and I can remember walking on that field, and there were 80,000 fans, the biggest stadium I’ve ever seen. When they say you see or hear sound or you see sound move, I did when we walked out on that field, and they were screaming, and it was just waves of sound, and I’m going “wow, oh man.” But, like any other game, once that whistle blows and the kickoff begins, it’s just another game. It was a tough game, and we got the ball last obviously, and were accused of running out the clock. In looking back at that time, it wasn’t so much we were running out the clock; we were holding the ball pretty well on the field, and we ran out of time. I think what we all anticipated was, well, you got to throw, you got to throw down field; you got to go for the box; you got to go for whatever it might be whether you lose or not. Ara’s (Notre Dame Coach Parsegian) take was that, hey, it was a game that they had to beat us to capture that National Championship. A tie wouldn’t necessarily do it for them, and you guys worked so hard to be able to get here, that I didn’t want you to lose the game. So we controlled the ball as best we possibly could, and we ended up in a 10-10 tie, and it was like kissing your sister. It was almost like a loss, nothing was really determined. And ultimately, here we are all these many years later, and we’re still talking about that game. If we would have won or if they would have won, no one would have cared, but since we tied, we still talk about it.

Of course, the second famous game that I wanted to ask you about was the Immaculate Conception. Where were you when Franco made that catch?

BLEIER: I was on the sidelines. Earlier, I was in the game along with Franco and so we were watching what was taking place. It was first down and 10 on the 30-yard line, and it was incomplete pass; and then the second down was incomplete pass, and the third down was incomplete pass. And all of a sudden, with what, 31 seconds or so on the clock? You know it was 4th and 10 on the 30, we have 70 yards to go, and it was like this is it. My thought was I can’t watch it. It was like disaster, I can’t watch it. I want to win. I got all of this stuff out of here, interruptions or whatever – and, oh, we scored, we scored, we scored. So, like 300,000 people said that they were at that game, and all watched it – I don’t believe that. I tell people, you don’t watch disaster taking place; I think you closed your eyes or you gave up hope at the time, and all of a sudden you saw it afterwards. Like everybody else now, the only way I remember it is by watching it on television or that film clip.

January 18, 1976. Rocky Bleier runs the ball upfield during Super Bowl X. (Vernon Biever)

Sticking with the Steelers, what are your memories of Pittsburgh Steelers Owner Art Rooney?

BLEIER: They’re all positives, and everybody’s got their Art Rooney stories. He was a man that made a difference within the city and with this club, and, he was a very gracious man. He always had time for his players, knew all his players by name, and he knew something about every one of his players and/or the media that were around him. He was an engaging fellow, a Damon Runyon kind of person. It was a time that I’ll never forget and I think a time for us who got a chance to play to get to know a man like him.

What are your memories of Chuck Noll?

BLEIER: My memories of Chuck are that he was a student of the game, who knew everything about the game. He wasn’t a player’s coach, meaning a buddy-buddy kind of guy. He had certain expectations and wanted you to live up to those expectations. He allowed his assistant coaches to do their job. He had a great insight into the game of what could be accomplished. He didn’t over-train his players, and his expectation was to get the most out of a practice that he could, without going through two hours-plus. I mean every practice was what could be accomplished time-wise, and you better get it done within that amount of time. So that was a great thing. I just thought it was the way it should be. Chuck broke down his successes, and there was always a reason why and it wasn’t necessarily because we had great games or we did great things. Sometimes it was because the opponent had bad habits and/or there was great individual effort by somebody. He was always teaching, trying to teach people an aspect of this game, and a lesson in life, how things work, and what he expected was for you to live up to the goals and the expectations that he had set for the team and for you specifically, and that basically was your job. He didn’t want to fine you, if there was a curfew, just be in on time and accept that responsibility as a professional player and try to become better within the power from which you have. That was Chuck. He always had an open door policy.

Yes, I sat in a few of his news conferences after games during that time.

During his news conference, he made a statement about the game, and tried to talk about the generality of the game, offense, defense, the opponents and so on. He never pointed fingers at a specific player that might have caused a loss or something, and it was always a team effort. That was his statement, and he always felt that covered every question you might have as a reporter. Whenever you want to get specific about a player and/or a play, or a turning point, his answers got shorter and shorter and shorter. And, he became very blunt. That was his press conferences.

Here’s my last question. How involved, if at all, were you with the movie “Fighting Back,” based on your book?

BLEIER: My involvement was as a technical advisor. They wrote the screenplay, and we talked about it before they wrote the screenplay. They talked about the movie, about my life. I have a nice story, but to make a movie out of it, it becomes somewhat difficult because where is the antagonist, the protagonist, the conflict? It’s a movie of overcoming obstacles and setting goals. So when Jerry McNeely wrote the screenplay, he said, “We’ll capture the essence of who you are with clarity and character. You can’t have more than four or five focal points, but I think that you will be pleased.” So, I spent a week in California and then was on the set here and got a chance to get a director’s chair with my name on the back, and that was about it.